APY lands. Image credit: Naomi Indigo

Arid Zone Monitoring

What is the Arid Zone Monitoring project?

The Arid Zone Monitoring project supports people and groups who are using track-based survey methods to monitor Australia’s desert fauna. The project aims to:

• Use this dataset could be used to map the distributions of desert species and look for trends in abundance over time.

• Provide guidance to support future sampling design and data collection.

• Showcase the work being carried out in the deserts, especially by Indigenous ranger groups.

• Lay the groundwork for creating ongoing, national-scale monitoring for desert wildlife.

Who is the Arid Zone Monitoring project?

The project is a collaboration between the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program (through the Threatened Species Recovery Hub) and over 40 partners. The partners are Indigenous ranger groups and Indigenous organisations, NGOs and NRM groups, government agencies and institutions, and individual researchers and consultants.

Karajarri ranger. Image credit: Nicolas Rakotopare

Image credit: Nicolas Rakotopare

Kiwirrkurra rangers. Image credit: Nicolas Rakotopare

Image credit: Jaana Dielenberg

Why do we need the Arid Zone Monitoring project?

Monitoring animal populations in Australia’s sandy deserts is challenging. Many animal populations are at low density, have patchy distributions, and boom-bust population cycles, making it hard to understand patterns when working at single site, or for short periods of time.

Many individuals and groups across Australia’s deserts have collected data using track-based methods (i.e. searching an area to record animal presence based on their tracks, scats, diggings, or other signs). Surveys have mainly been carried out to describe the species present in an area. Track-based surveys are also excellent opportunities for people to get out on Country, share skills and pass knowledge between generations. Some of the information from past track-based surveys had been collated, but most was still dispersed across the many groups that gathered the data, and therefore inaccessible for national-scale analyses.

If the local-scale data collected by many independent groups were collated into a single dataset, the combined dataset could be used to describe species distributions and changes over time, across Australia’s deserts. Collaborative track-based monitoring could contribute to regional or national monitoring of native and feral species, improve our understanding of environmental processes, and allow us to monitor the outcome of fire and feral animal management, and other actions.

Acknowledgements

The Arid Zone Monitoring Project was funded by the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program through the Threatened Species Recovery Hub. The Project distils the very large collective effort of many people – Traditional Owners, Indigenous rangers, university researchers, consultants, and government staff - who live and work in Australia’s deserts. It has been a privilege for the project team to be a small part of their deep commitment to caring for Australia’s deserts.The full acknowledgments are available in the “More Information” tab.

Antara-Sandy Bore Indigenous Protected Area. Image credit: Naomi Indigo

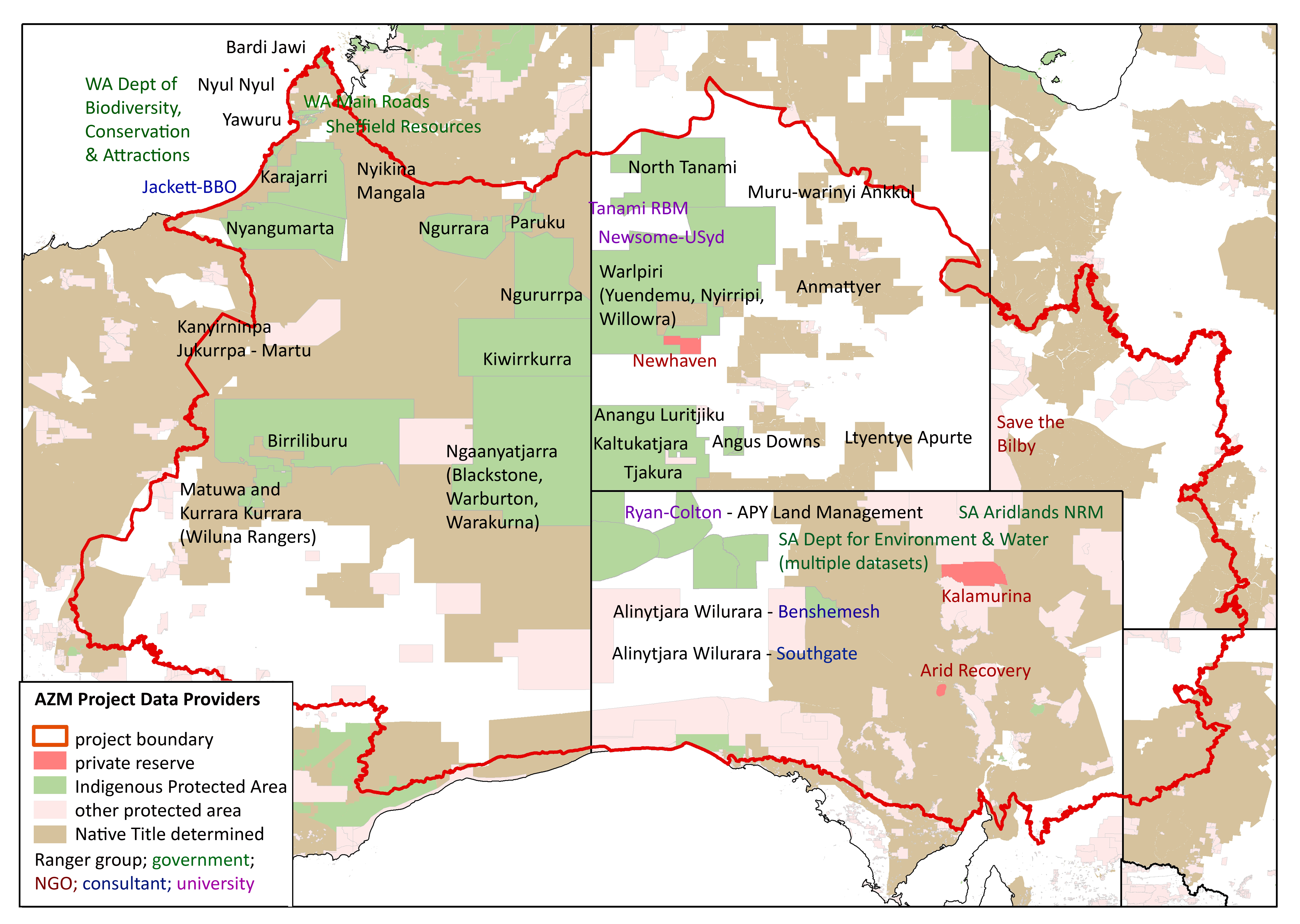

The Arid Zone Monitoring project covers 3,273,140 km2 of Australia’s arid and semi-arid regions. This area is looked after by Traditional Owners and Indigenous Rangers, NGOs, and government agencies. Many of these groups, as well as independent ecologists and consultants, have carried out wildlife surveys by searching for tracks, scats and diggings using standardised methods.

Project area

The project area includes all of Australia’s sandy desert bioregions, with an extension in the northwest to include the Pindanland subregion (Dampierland bioregion), and another extension into the Gascoyne and Pilbara bioregions. Defining the project boundary is necessary for setting the ‘environmental envelope’ used in distribution modelling.

Ngururrpa IPA rangers

Bringing the data together

The Arid Zone Monitoring National Dataset is a collation of 69 datasets, shared by 37 different groups and individuals who have carried out track-based surveys across Australia.

Where is the data from?

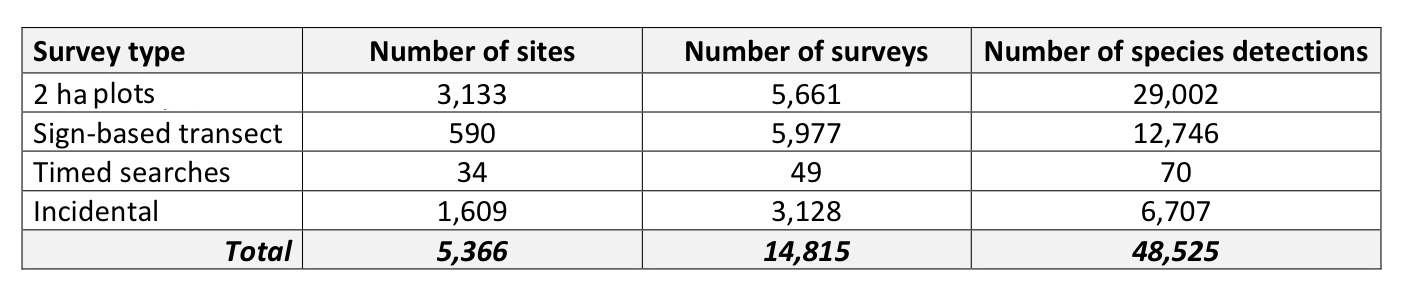

South Australian partners shared data from the greatest number of sites and surveys, followed by Western Australia and the Northern Territory. The number of partners that shared data varied from 16 for WA, 14 for the NT, one for Qld and six for SA.Overall, the project partners detected almost 50,000 species records, from almost 15,000 surveys, carried out at over 5,300 unique sites across the desert.

Survey effort and records

Records of animals were made using several different survey methods. The most common method was a 2 ha plot survey (sometimes called a sign survey, track survey, sand plot, cybertracker survey or Tracks App survey). In a 2 ha plot survey, observers search a 2 ha area for signs of animal presence and record information about the habitat or tracking conditions.Transect surveys, where observers search for tracks along a linear path, were also common. Timed searches are when observers look for animal signs for a set length of time. This includes searches carried out on foot or by a slow-moving vehicle. Some records were ‘incidental’, where observers noticed and recorded the track, scat or digging, but they were not carrying out a formal survey.

In some surveys, observers recorded which species were absent, as well as those that were present. This absence information can be very useful is some types of analyses. Information on absence data is summarised in the Arid Zone Monitoring Project report.

Jacko Shovellor, Karajarri ranger. Image credit: Nicolas Rakotopare

APY lands. Image credit: Naomi Indigo

Martu child pointing at Mankarr tracks. Image credit: KJ

Punmu Rangers. Image credit: KJ

APY lands. Image credit: Naomi Indigo

Track-based surveys were pioneered by ecologists working with Traditional Owners in the 1980s, but the method spread, and is now used by many different groups working in the deserts.

The Arid Zone Monitoring National Dataset contains records for the period 1982 to 2021, although there are few records in the first decade or so. Early data were mostly from South Australia. Data began to accumulate in Western Australia and Northern Territory starting from early 2000s.

Image credit: Naomi Indigo

Image credit: Nicolas Rakotopare

Ngurrara rangers. Image credit: Hamsini Biljani

Image credit: Jaana Dielenberg

Image credit: Nicolas Rakotopare

Track-based surveys were pioneered by ecologists working with Traditional Owners in the 1980s, but the method spread, and is now used by many different groups working in the deserts.

Over time the types of organisations or individuals carrying out surveys has shifted. The data shared by the South Australian government is based on work by several ecologists, consultants and others who developed the 2 ha plot method in the 1980s. More recently, Indigenous groups, NGOs and NRM groups began using the method more widely.

Umuwa, APY Lands, May 2021. Image credit: Sarah Legge

Tracking near Umuwa. Image credit: Naomi Indigo

The AZM National Dataset contains records of 76 species: 27 native mammal species, 11 introduced mammal species, 4 bird species and 34 reptile species.

The dataset also contains records where sign was not attributed to a species, but was identified to genus level (3 mammal and 5 reptile genera), or a higher group level (3 mammal groups, 1 bird group, 5 reptile groups, 1 frog group and 1 invertebrate group).The maps summarise the detections of this species in the AZM dataset. Each blue dot shows a survey site where the species was records; the grey dots show all the other sites that were surveyed, but where the species was not recorded. These records were made by Indigenous Ranger groups, land councils, NGOs, government agencies and university researchers. It is possible that extra surveys have been carried out that have not yet been shared. If you see ‘gaps’ in the maps that you could fill by sharing your data, let us know.

Overall:

The map shows the average animal detection rate across all surveys carried out in each bioregion, since the 1980s. Detection rates for the animal have been highest in bioregions with the darkest blue shading.

Detections over time:

The maps summarise the detections of the animal over time in the AZM dataset. Each blue dot shows a survey site where the animal was recorded in that decade. The grey dots show all the other sites that were surveyed, but where the animal was not recorded in that decade.The habitat suitability model can tell us about where the animal is most likely to be found. The analysis considered climate factors like annual, seasonal and daily temperature and rainfall; landform factors like elevation and slope; soil factors; and habitat factors like the amount of green vegetation (NDVI) and fire frequency.

Caveats: The map only shows habitat suitability inside the Arid Zone Monitoring project boundary, but some desert species are also found outside this area, and may even be more common away from the deserts. The habitat suitability model does not predict well in areas where there has not been any sampling, for example in parts of the Great Sandy Desert and the Great Victoria Desert; getting more survey data from these areas would improve the models.

Karajarri. Image credit: Ann Jones

The method also works best for larger-bodied animals with tracks that are easily identified, such as mulgara, goannas, bilby, cats, dingoes, and camels. If you want to monitor smaller animals, like small mice and dasyurids (e.g. dunnarts), small reptiles, and small birds, then there are better survey methods to use.

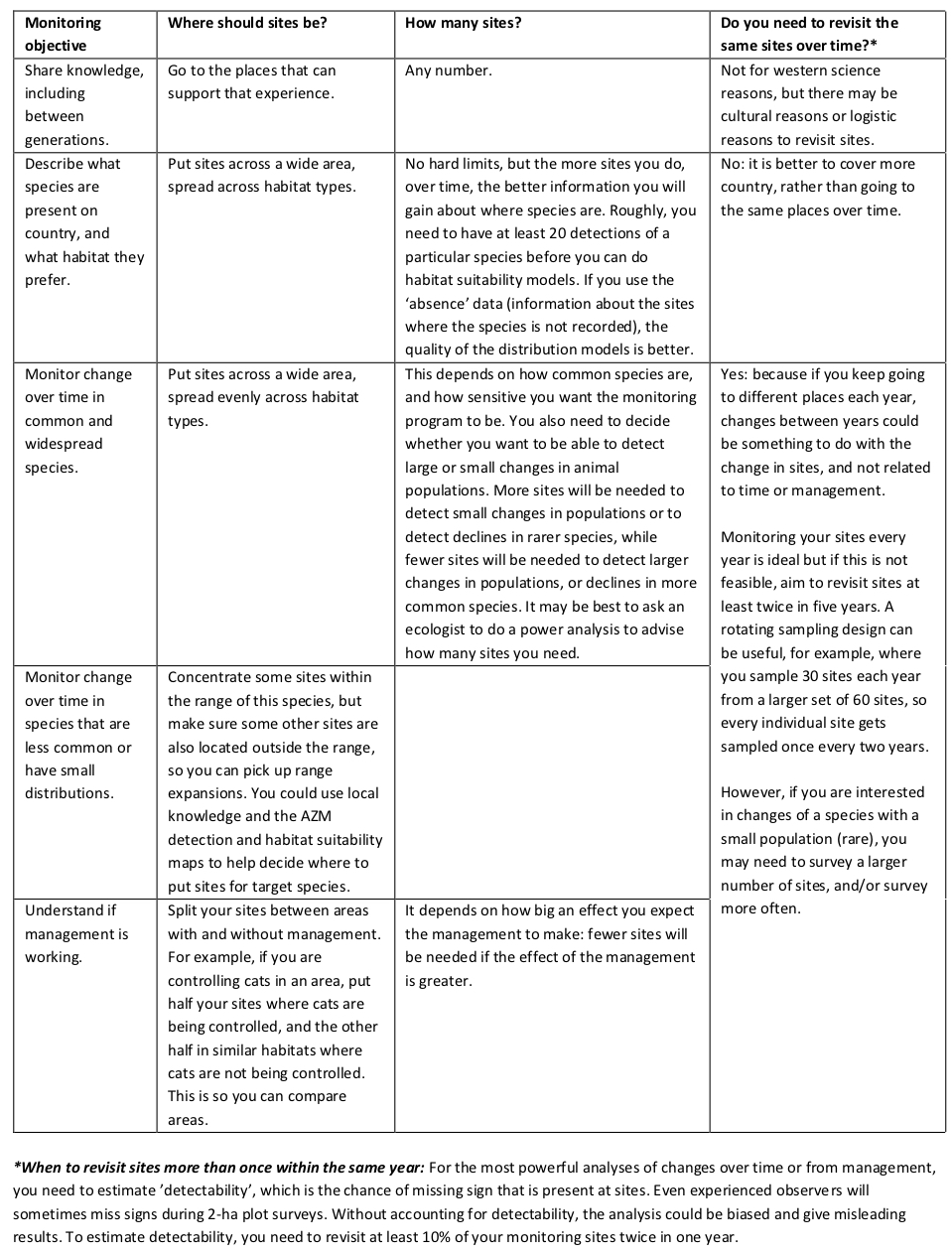

Monitoring objectives

Like all surveys, track-based surveys need to be designed carefully to record data that are useful for answering the questions your team is interested in. It is important you decide why you are monitoring early (this is called the monitoring objective). Knowing your monitoring objective affects decisions about where to survey, how many sites to survey, and how often to re-visit them. It is best to get advice from an experienced ecologist to design your survey, but general guidelines are:

Yukultji Napangati. Image credit: Jaana Dielenberg

Martu kids with Marita. Image credit: KJ

Overall rules of thumb for monitoring programs at local, regional and national scales

Try to keep sites more than 4-5 km apart from each other, so that your samples are ‘independent’, and it’s unlikely that the same individual animals are leaving prints across the sites.For a monitoring program at the property or IPA scale, sampling 30 sites (from a set of about 60 sites) each year, split across the main habitat types, should pick up changes in the detections rates or occupancy of most species. If you increase the number of sites sampled in a year, you will have a greater chance of picking up change, especially if the change is small. If there are rare species that are targets for the survey, you may need extra sites clustered in the area where that species occurs – your team may use exiting species distribution maps, AZM maps or local knowledge to find where this is in the survey area.

For a regional monitoring program, about 200 sites are needed to have a high chance at detecting moderate (~30%) declines for most species (based on analysis of South Australian data). These sites could be spread across several IPAs, national parks, and other properties, so that any one team is sampling only part of the whole set of sites.

Karajarri rangers. Image credit: Nicolas Rakotopare

Punmu Rangers. Image credit: KJ

There are different ways of collecting track-based data:

• Transect searches – a stretch of track is searched systematically.

• Timed searches – trackers wander through an area in any direction for a set amount of time. E.g. click here.

Looking for animal signs on the road/driving track:

If the 2 ha plot is near a track, keep the search area off the track itself, by at least 30 m. This is because some animals (such as dingoes and foxes) prefer to use roads, and other animals avoid them. The sign along roads is a biased sample of what is present. To get a good sample of all animals present, set up a 100m transect along the track near to the 2 ha plot, and record the sign on this transect as well as the sign in the 2 ha plot. It is very important to keep the data from the plot and the road transect separate in your datasheet, so that biases can be taken into account during analysis.Different methods (2 ha plot vs transect) can be accommodated in analyses that collate data from many people and groups, but differences in data recording fields, and inconsistencies in data quality, can be a real problem. Streamlining data collection to a core set of fields that are recorded consistently makes it much easier to combine track-based data from many different people and groups. To that end, the Arid Zone Monitoring project worked with several tracking experts to design a standard data recording sheet that could be used nationally, regardless of the track-based survey method used.

More information on this topic:

To download the standard data recording sheet with instruction, click here.

To read the full report that details tracking experts’ perspectives on data collection template, click here.

To read an example of a survey done used timed searches, click here.

To download the preferred data entry templates to store your data, click here.

Looking for tracks near Uluru. Image credit: Jaana Dielenberg

Links and reports

The resources available on the National Environmental Science Programme (NESP) Threatened Species Recovery (TSR) hub website are:

Reports:• AZM Project Report

• AZM Project Summary

• APY Lands field trip report

Monitoring design guidance:

• For 44 species or groups

Species Profiles:

• AZM Monitoring design for track-based surveys

• AZM Summary-Designing a monitoring program for South Australia

• Detailed example of how to design a regional monitoring program (coming soon)

• Detailed example of the design of a national monitoring program (coming soon)

• Detailed analysis of features that affect detectability (coming soon)

Data collection guidance and templates:

• AZM Report on perspectives on tracking data

• AZM Data recording sheet and instructions

• AZM Data entry templates

Further reading

Skroblin, A., Carboon, T., Bidu, G., Chapman, N., Miller, M., Taylor, K., Taylor, W., Game, E.T. and Wintle, B.A., (2021). Including indigenous knowledge in species distribution modeling for increased ecological insights. Conservation Biology, 35(2), 587-597.

Moseby, K.E., Nano, T. and Southgate, R. (2009). Tales in the Sand: A guide to identifying arid zone fauna using spoor and other signs. Ecological Horizons, South Australia.

Legge, S., Lindenmayer, D. B., Robinson, N., Scheele, B., Southwell, D., and Wintle, B. (2018). 'Monitoring Threatened Species and Ecological Communities.' CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne, Australia.

Leiper, I., Zander, K. K., Robinson, C. J., Carwadine, J., Moggridge, B. J., and Garnett, S. T. (2018). Quantifying current and potential contributions of Australian indigenous peoples to threatened species management. Conservation Biology 32, 1038-1047.

Contact us

For more information or enquiries, please contact Sarah Legge on AridZoneMonitoring@gmail.com

Antara-Sandy Bore Indigenous Protected Area. Image credit: Naomi Indigo

Acknowledgements

The Arid Zone Monitoring Project was funded by the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program through the Threatened Species Recovery Hub. The Project distils the very large collective effort of many people – Traditional Owners, Indigenous rangers, university researchers, consultants, and government staff - who live and work in Australia’s deserts. It has been a privilege for the project team to be a small part of their deep commitment to caring for Australia’s deserts.The data collation and analysis for the Arid Zone Monitoring Project was carried out by Naomi Indigo, Anja Skroblin, Darren Southwell, Tida Nou, Liam Grimmett, David Wilkinson, Diego Brizuela-Torres, Taleah Watego, Katherine Moseby, Rick Southgate, and Sarah Legge. The project website, which displays and organises some of the project’s key outputs, was developed by Alys Young. The project has relied heavily on the Hub’s communications team of Steve Wilson, Mary Cryan, Nico Rakotopare and Jaana Dielenberg. Nelika Hughes advised us on data management options; the EcoCommons team and Martin Westgate helped us get the website off the ground; Chris Fenwick and Heather Christensen were invaluable project management support. We thank the Hub’s Indigenous Reference Group for their guidance (Cissy Gore-Birch, Stephen van Leeuwen, Oli Costello, Teagan Goolmeer).

The project builds on the efforts of individuals who have used, or advocated for, coordinated track-based monitoring for many years, and who provided valuable advice to the project. As well as Katherine Moseby and Rick Southgate, this includes Rachel Paltridge (Kiwirrkurra); Laurie Tait, Kim Webeck, Sam Rando and Thalie Paltridge (Central Land Council); Danae Moore (AWC); Joe Benshemesh (Maralinga); Dorian Moro (Wiluna Rangers); Martin Dziminski (WA DBCA); Chris Curnow (WA Rangelands); Peter See (10 Deserts, Country Needs People); Pete Copley, Cat Lynch and Dan Rogers (SA DENR); Rob Brandle (SAAL NRM Board). Many more people have made the project possible, by collecting and sharing data, supporting data collection by rangers, facilitating project communication, and by being sounding boards. A complete list is available in the full report, and we thank them all for being part of this project.